Landscape Terms for a Water-Wise World

At Superbloom, we’ve been thinking a lot about the language we use to talk about water—how it moves through landscapes, how we design for it, and how we describe those designs to clients, collaborators, and communities. As a landscape architecture studio rooted in the arid West, these terms matter. They shape how we communicate intent, set expectations, and build landscapes that respond to real ecological pressures.

We pulled together this guide to help clarify some of the most commonly used terms in water-conscious design—both for ourselves and for the people we work with. Whether you’re a city planner, a developer, or just curious about climate-responsive landscapes, having a shared vocabulary helps ensure we’re all designing toward the same resilient future.

Drought-Tolerant, Native, or Just Confused? A Field Guide to Water Words

In the arid West—especially in places like Colorado—water is not just a resource; it’s a design constraint, a budget item, a sustainability benchmark, and sometimes, a political topic. Every decision we make in landscape design, from plant selection to irrigation strategy, must reckon with the fundamental truth: we live in a dry pretty dry place.

And it’s not just the scorching summers—Colorado’s dryness is year-round. How often do we hear people describe our winters as “sunny and dry,” a welcome contrast to the sometimes brutal, wet East Coast winters? While we might relish the clear skies and mild temperatures, the truth is that our landscapes are constantly operating under water stress, no matter the season.

With so much pressure on water systems and growing awareness around climate resilience, a whole vocabulary has emerged around how we design landscapes in relation to water. But with so many overlapping terms—drought-tolerant, xeriscape, native, sustainable, water-efficient—it can be hard to know what each one really means, and why it matters.

Commonly Used Water-Related Landscape Terms

Xeriscape

Often misunderstood as “zeroscape,” xeriscaping is actually a thoughtful approach to designing landscapes that minimize water use without sacrificing beauty. The root of the word xeriscaping comes from the Greek word “xēros” (ξηρός), which means “dry”, combined with “landscaping.” So, xeriscaping literally means “dry landscaping.” So if we go off the literal meaning of xeriscaping, most of the landscaping done in Colorado would fall under this category. Perhaps that’s why the term was coined in Colorado almost 50 years ago by Nancy Leavitt in conjunction with the Denver Water Department. It’s worth noting that while the term originated with a specific water-conservation focus, over time it has come to encompass a broader philosophy that includes soil health, native plants, efficient irrigation, and aesthetic design—not just dryness. While it’s a useful concept, xeriscaping is often misused, and can conjure images of lifeless gravel yards—something we’re actively working to move beyond. At Superbloom, we believe xeriscaping doesn’t have to be a sum zero equation. Our goal is to create landscapes where everyone wins—from our clients and communities to pollinators, soil systems, and future generations.

Native

Native plants are those that occur naturally in a particular region or ecosystem. These plants are often well-suited to local water availability, climate conditions, and soils. However, “native” does not automatically mean low-water or drought-tolerant—especially in disturbed urban environments where soils and hydrology have changed dramatically.

Sustainable

A widely used term that refers to landscapes that minimize resource use, including water. While a good starting point, “sustainable” often stops at doing less harm rather than creating more ecological good.

Drought-Tolerant

Describes plants that can survive with little water. This is a helpful descriptor, but can be too narrow—many plants tolerate drought but still benefit from strategic irrigation or seasonal rainfall.

Water-Efficient / Low-Water

These terms typically focus on the amount of water used in a landscape. While they’re useful for tracking metrics or performance goals, they can lack context about plant health, biodiversity, and resilience.

January 22, 2026

Creating Interest in Winter Interest

October 19, 2022

Nature Play: Nurturing a Lifelong Love for the Outdoors

August 17, 2022

Design Meets Science in the Vision for Warm Springs Preserve

February 20, 2022

Populus Hotel Landscape Design Kicks-off with Studio Gang Architects

March 14, 2025

Bluff Lake Nature Center Ground Breaking

January 2, 2025

Superbloom’s 2024 Plant of the Year: Kinnikinnick!

Related Posts

January 22, 2026

Creating Interest in Winter Interest

Winter isn’t a pause—it’s preparation. Discover how designing for winter…

December 4, 2023

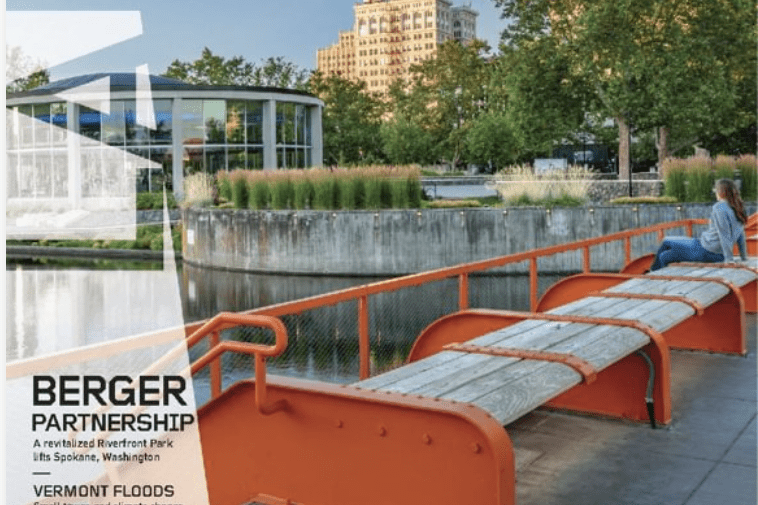

Landscape Architecture Magazine Highlights Superbloom’s 1881 Park Project

In the December 2023 issue of Landscape Architecture Magazine, Timothy A.…

October 19, 2022

Nature Play: Nurturing a Lifelong Love for the Outdoors

As landscape architects, our designs can evoke a strong sense of place and…